Vijayanagara: Deeper and More Informed Praise for This Game

Zeroing in on why I find myself thinking about Vijayanagara: The Deccan Empires of Medieval India day and night.

This is adapted from the script of Episode 98, “ˆLight and Get Away, It’s the Fall Small Games Preview.”

I’m taking you back to medieval India for deeper thoughts on my initial take on Vijayanagara: The Deccan Empires of Medieval India 1290-1398 from GMT Games. Outside of obsessive Faraway play on BoardGameGeek, this is my heartthrob. I’m now at the tail end of two more parallel games on RallyTheTroops.com and have a better handle on why I find myself thinking about it day and night.

I ran across a helpful quote from Chris Farrell from the July 14 edition of his superb Substack newsletter, Illuminating Games. In the course of talking about Red Dust Rebellion, Jarrod Carmichael’s weighty futuristic entry into the couinterinsurgency, or COIN, system , he said this: “The defining feature of COIN is that you can never really get anything done. You’re at the mercy of the action deck for your activations, and actually taking a turn (which could be a trivial limited op) paralyzes you for the next card so you can never truly gain momentum. You can’t do anything complex or have much of a plan.”

Vijayanagara is built on a system called the Irregular Conflict Series, which is an offshoot of the COIN system, but everything he says here I find is also true of Vijayanagara. The forced cool-down of having your empire’s action counter stuck in the Ineligible box for what feels like decades is agonizing as you watch your eligible enemies disassemble your board position. Throw in the volatility of the events and you can quickly feel like you’re in a lifeboat with one oar, 10-foot swells coming at you from all directions.

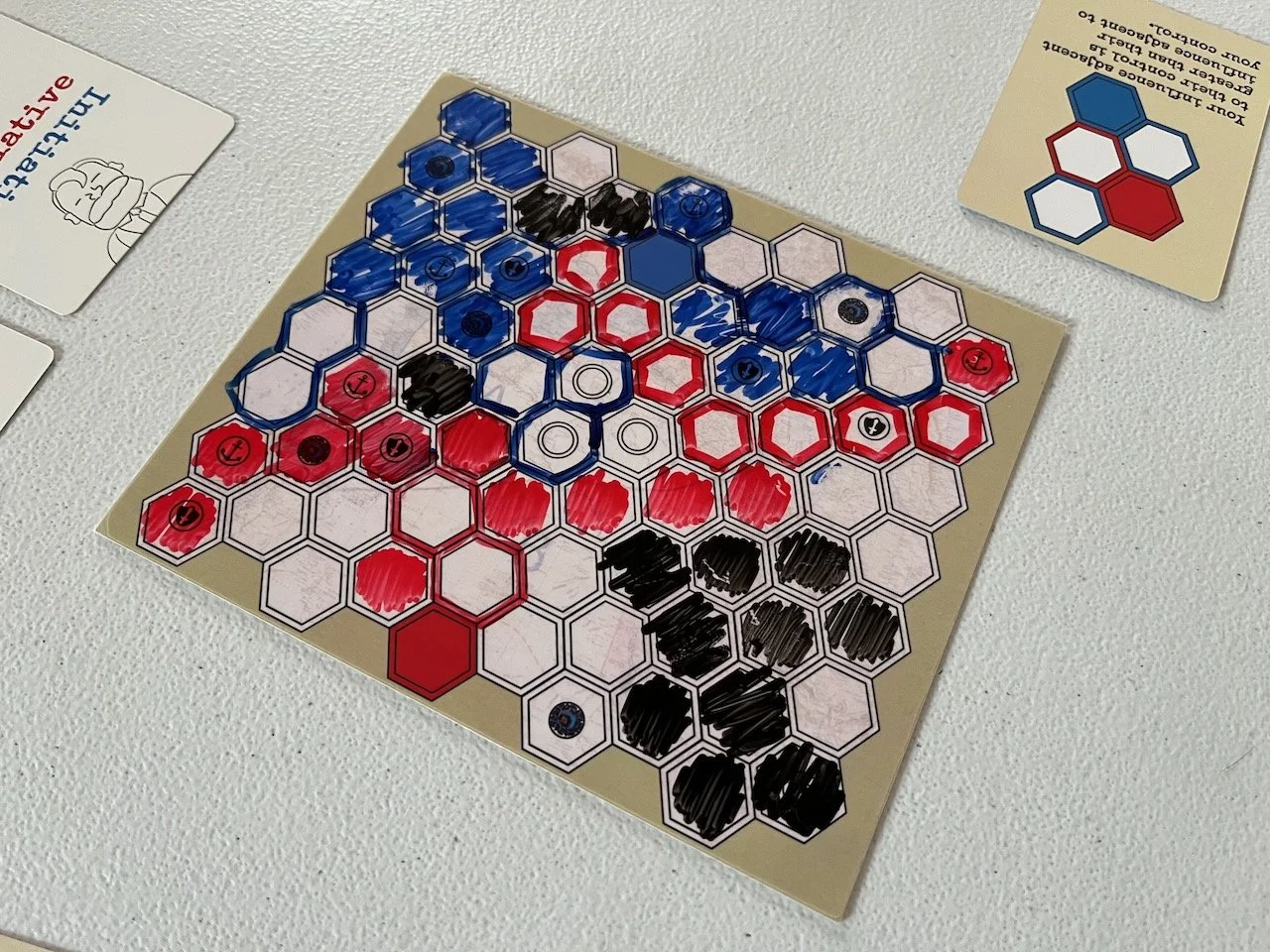

Vijayanagara: Deccan Empires of Medieval India - In the latest of my series of matches against Michal and David, I’m playing as the Bahmani Kingdom (green) and find myself in an unusually fierce contest for the lower regions of the map.

But this is a feeling I’ve come to embrace as a beginning-level player of this game. A lot of it has to do with how my brain works: It takes me an immense amount of effort and repetition — and even conscious emotional regulation — to be responsible for an outcome in long, hard-fought games where there’s a clear and unforgiving line from the decisions you made to the end result. There’s a reason I don’t fuck with chess.

For me, in-game chaos that hides perfect knowledge and short-circuits perfect plans is like a jester that lifts the anxiety of analysis paralysis and pleasantly scumbles what would otherwise be a picture of incompetence and ineffectual play. It pleasantly confuses the killjoy in my head that tells me the poor job I did was the only story.

As somebody who craves a mix of pure experience, exploration, surprise and the occasional win, the jester of fate shows me happy troughs in between the waves where I can make a satisfying and clever tactical move without seizing at the terror of being responsible for a Grand Scheme. As I reflect on a loss, I can savor ideas for improvement in digestible pieces because they sit alongside a comforting serving of “Well, there wasn’t shit I coulda done about that.”

Vijayanagara is giving it all to me right now: The spark of competition, the right level of detail and weight, an intriguing time and place, and the delight of a rambunctious story I’m only partially responsible for writing.

Other notes on what is making this so fun for me:

1. Getting to play it on Rally the Troops: My opponents in the two simultaneous virtual games are spread from Vancouver to Krakow to Perth. That’s a lot of time in between turns to study and savor the board. The deliberative pace helps me. I can ignore the first stab of disappointment at seeing one of my cherished regions overtaken by a neighbor who I thought I had under control and think about it a second time, a third. Put me at a table where that’s happening, I flounder and sink under the pressure, making unfocused and spastic moves. This mode of play is a perfect midpoint between merry skull-bashing and the contemplative.

2. I only knew about Timur, also known as Tamerlane, in relation to Eurocentric history. I think at one point the Pope or somebody sent an emissary to him because Rome thought the Mongols were Christians and might help them subdue the Levant for Jesus and loot? Now I’m looking up figures and cultures from all over Asia as their own galaxy with its own centers of gravity instead of as a distal chapter in the movement of European kings, which I think is one of the things the design team wanted to get boardgamers to think about.

3. I love how the game has historical acts that match the play, mimic the arc of history, and force an interesting finish for everybody: It’s great to be the Sultanate in the early game, when you can crush almost anything in your line of sight and the Mongols haven’t shown up yet. It’s great to be the breakaway Bahmani Kingdom in the middle game, when you can carve off fat servings of the Sultanate’s provinces as their grip starts to weaken and use your moneymaking ability to hassle the nascent Vijayanagara with cavalry strikes. In the late stage, enjoy being a Vijayanagaran Rajas who can vent north over the board, your slow-building strength manifesting right as your rivals have just about punched themselves out.

There’s a mix of experience levels in the two separate games I’m playing, but in each one, the game’s aggregate messiness somehow pushes the cluster of victory point markers close enough to each other at the finish so that even a faction that got ground into the dirt three turns ago can tip the scales or even seize the win before the final Mongol assault on Delhi closes the whole thing out. As to whether this forgiving bit of slack is built into the design as a leveling device or a function of my two groups’ general experience or playstyle, I’m not certain.

4. I love the asymmetry, both in how it models its setting and incentivizes each of the sides in this 100-plus-year push and pull. After two plays as the mighty Sultanate, I tried commanding the Bahmani Kingdom. It was a delicious new vantage point that required new thinking; I wasn’t a guy who could throw tens of thousands of troops around the board anymore in between feeding bits of meat to the hunting falcon on my wrist.

I had to learn the nuances of the Deccan Influence track, a specialized part of the challenger kingdoms’ dashboards that forces the Vijayanagara and Bahmani players to think about when and where they should take a break from playing cat-and-mouse with the Sultanate and instead chuck something mean and pointy over their neighbor’s fence. The Bahmani’s influence track has different motivations and rewards than Vijayanagara’s. With how much Rally the Troops lightens the mechanical burden, it’s easy to step into different roles and shortcut to thinking about the possibilities of what you can do instead of how you can do it.

I have a pledge on GMT’s website for the second printing of this game. I love everything thing about it and I want a physical copy so I can also play it solo whenever I like using the bot decision cards for NPKs — non-player kingdoms. This game found me at the right time and I intend to make countless circuits across its engaging and hotly contested green expanse.

Sykes-Picot First Play: I’m Glad I Can Erase This Awful Mess I Made

I did a coloring project and congratulations, you now live in *checks notes* Iraq. My first play of Sikes-Picot: The Secret Treaty to Partition the Ottoman Empire from Hollandspiele.

In the critical media coverage I read extensively in the buildup to the 2003 war in Iraq, I remember learning that one of the many foundational problems was that Iraq, as we conceive of nation-states, had been sort of made up at the tail end of World War I when France and Britain took out the red and blue pencils to decide who would administer what. The “what” being hastily drawn “countries” whose lines did not take into account the cultural, tribal and religious landscape they were marking off. It was a powderkeg that exploded in a 1920 revolt and has been a-sploding ever since.

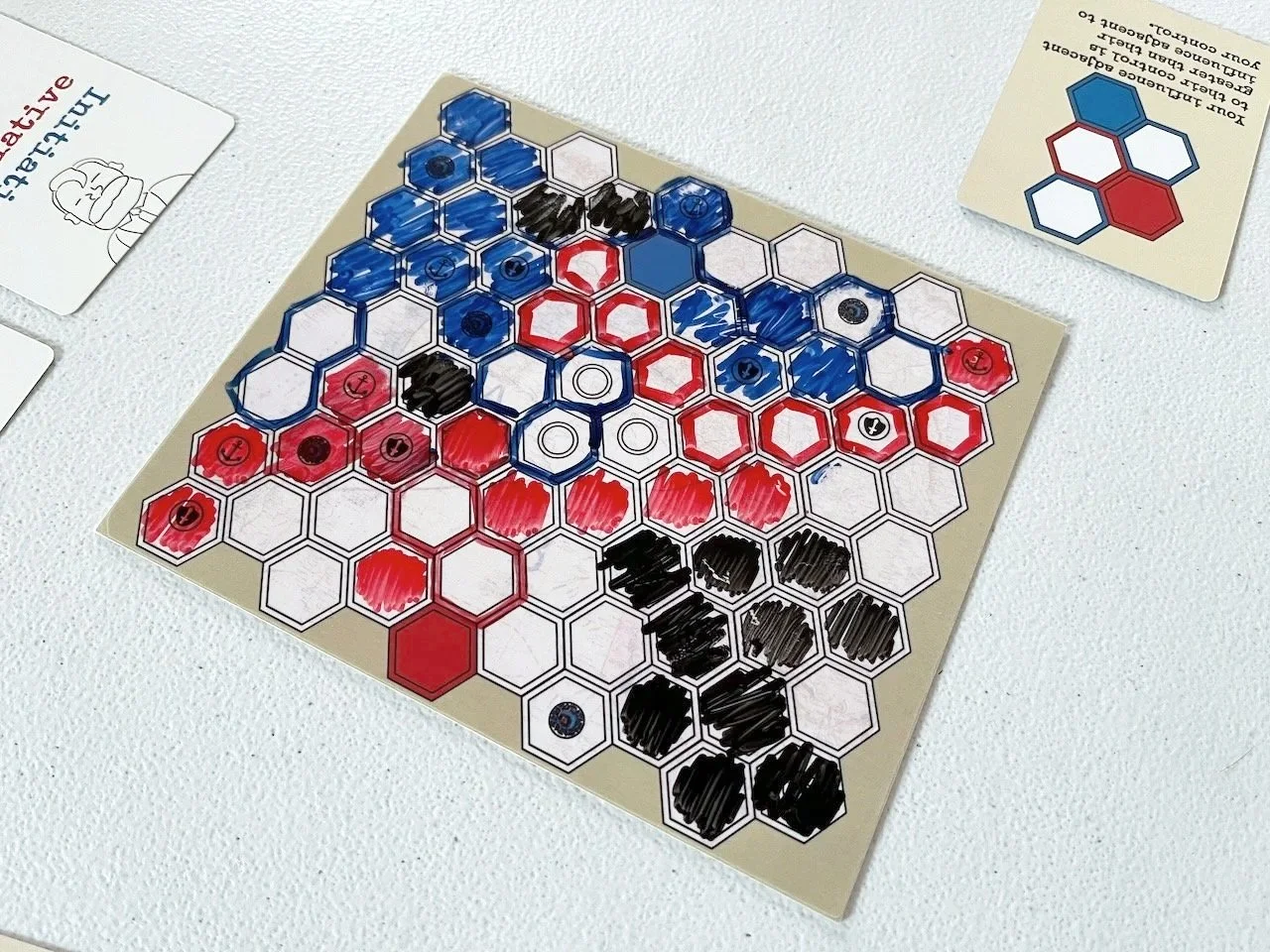

Sykes-Picot: The Secret Treaty to Partition the Ottoman Empire from Hollandspiele Games; the state of the board after two turns, with red territory (Britain), blue territory (Franch) and black territory (international control) indicating that we’ve probably already made a hash of things.

The diplomatic point men for this imperial Turkey carving were Mark Sykes on the British side and Francois-George Picot on the French side of the table. You and your opponent sit in the roles of these two men; you even get red and blue markers in the box and a dry erase board as you duel to lock down key shipping, strategic and cultural zones.

The mechanical piston that drives this duel is a trick-taking card game: Both the winner and the loser of each trick will get to change the map in some important way, because colored hex patterns appear on every card. There’s the straight-ahead possibility of leading high to simply make sure you get to influence or control the big group of hexes on the winning card, but the player who loses the trick gets pick from a menu of options that allow them to subtly improve their position or degrade yours, because — and this is an interesting touch — whoever executes a hex pattern does it in the color indicated by the card, not necessarily the color of their country. So you can tack some pretty bogus geometry into the middle of the opponent’s scheme.

Sykes-Picot: I’m playing as the Brits, but almost all the card effects from my hand have the potential to expand French influence or control. Or I could put that two of stars into play and risk some of the board falling into international control.

I first encountered this win-a-trick-you-need-but-set-off-an-effect-you-don’t-want design touch when I messed around with The Fox in the Forest a few years back. Here it was again, except in a starched collar, hiding its smile behind a raised porcelain cup as you quietly colored in everybody’s next long-term problem.

Keep in mind I’m talking about some of this action speculatively. I made contact with game designer Brooks Barber on Discord when I hailed a game design group asking if any of them had a title available I could look at and talk about. He raised his hand. Ta-da. A title from the maverick and inventive Hollandspiele imprint no less, which I’ve been overdue to sample.

Except in my enthusiasm, I forgot that moving to this part of the world made me a solo player. My opponent crapped out after the second round. (See: Hazards of external dependencies.) A bit of intention, curiosity and focus across the table is so critical for a two-seater game.

Sometimes I feel like a goddamn child who can’t remember anything, thinking I’m going to buy some “magic game” that’s going to create interest where there isn’t any, like I don’t have the dusty carcasses of previous multiplayer titles stacking up in the spare room. You think I’d learn.

Anyway, what I’m talking about here are intriguing things where my limited experience seems to point.

For one, that dry-erase board was filling up fast. The cards used for tricks get removed from the game. It was easy to see how two people could grind their teeth quite a bit playing this as a straight-ahead competitive area control game as the board closes. The diplomat who can track and analyze the dwindling possibilities could make their opposite’s life pure hell.

Except: The rules also suggest more fluid spaces to feel out. There are rules for negotiation — a dimension my exhausted playtester and I never even tried as we were just learning the basics. OR: As the designer also reminds us, you can also choose to play cooperatively.

Would that include, for example, using the abstracted dry-erase board to see if you challenge each other to fill it in while leaving key cultural sites alone? There seems to be explicit permission for creative subversion, a chance to play in an imperial sandbox without being bound by imperial logic. Unfortunately, the intriguing nuance of Sykes-Picot will remain hidden from me as long as keener opponents do. It is my hope to explore this fascinating and tragic duel again.