Sykes-Picot First Play: I’m Glad I Can Erase This Awful Mess I Made

In the critical media coverage I read extensively in the buildup to the 2003 war in Iraq, I remember learning that one of the many foundational problems was that Iraq, as we conceive of nation-states, had been sort of made up at the tail end of World War I when France and Britain took out the red and blue pencils to decide who would administer what. The “what” being hastily drawn “countries” whose lines did not take into account the cultural, tribal and religious landscape they were marking off. It was a powderkeg that exploded in a 1920 revolt and has been a-sploding ever since.

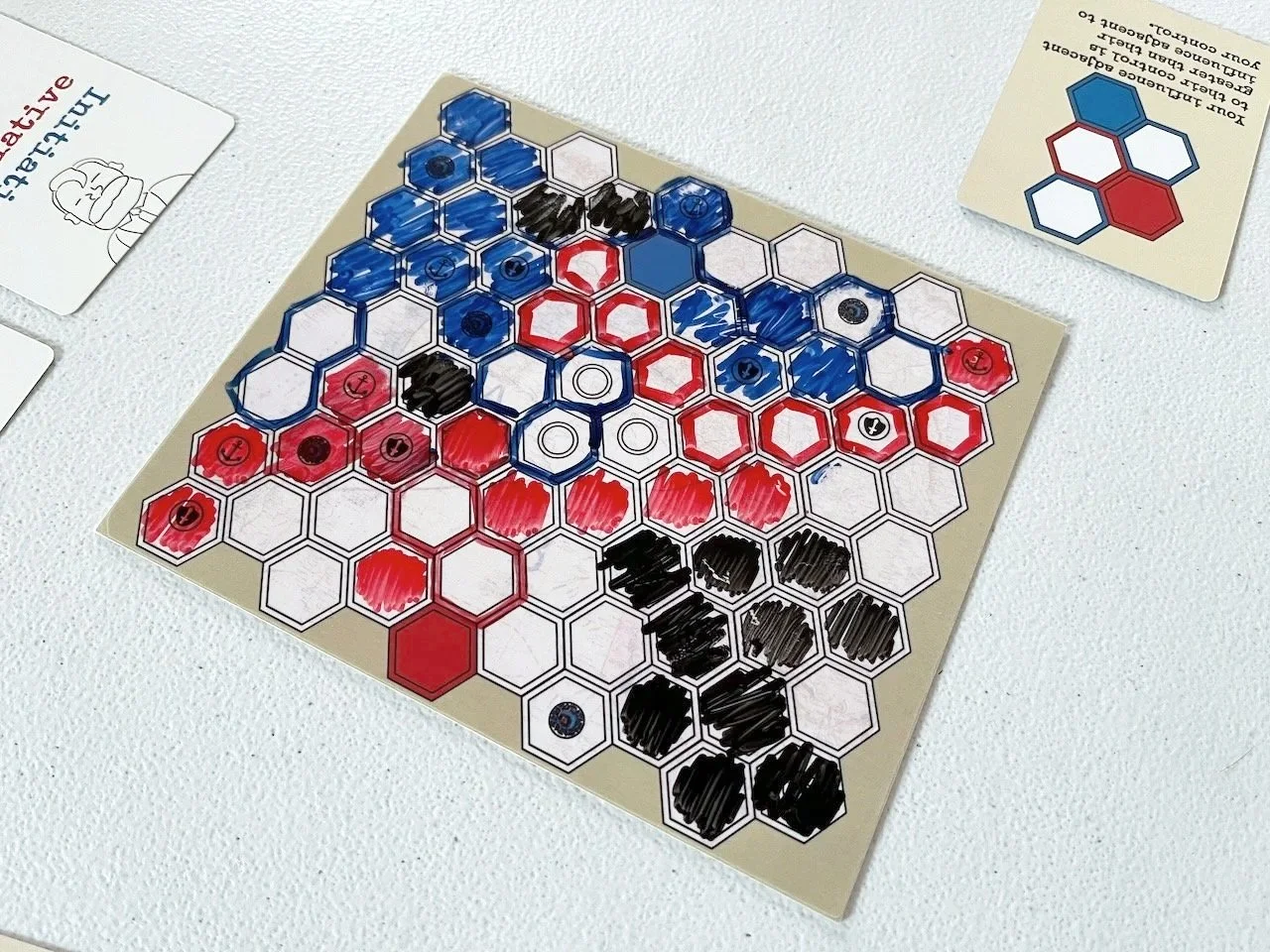

Sykes-Picot: The Secret Treaty to Partition the Ottoman Empire from Hollandspiele Games; the state of the board after two turns, with red territory (Britain), blue territory (Franch) and black territory (international control) indicating that we’ve probably already made a hash of things.

The diplomatic point men for this imperial Turkey carving were Mark Sykes on the British side and Francois-George Picot on the French side of the table. You and your opponent sit in the roles of these two men; you even get red and blue markers in the box and a dry erase board as you duel to lock down key shipping, strategic and cultural zones.

The mechanical piston that drives this duel is a trick-taking card game: Both the winner and the loser of each trick will get to change the map in some important way, because colored hex patterns appear on every card. There’s the straight-ahead possibility of leading high to simply make sure you get to influence or control the big group of hexes on the winning card, but the player who loses the trick gets pick from a menu of options that allow them to subtly improve their position or degrade yours, because — and this is an interesting touch — whoever executes a hex pattern does it in the color indicated by the card, not necessarily the color of their country. So you can tack some pretty bogus geometry into the middle of the opponent’s scheme.

Sykes-Picot: I’m playing as the Brits, but almost all the card effects from my hand have the potential to expand French influence or control. Or I could put that two of stars into play and risk some of the board falling into international control.

I first encountered this win-a-trick-you-need-but-set-off-an-effect-you-don’t-want design touch when I messed around with The Fox in the Forest a few years back. Here it was again, except in a starched collar, hiding its smile behind a raised porcelain cup as you quietly colored in everybody’s next long-term problem.

Keep in mind I’m talking about some of this action speculatively. I made contact with game designer Brooks Barber on Discord when I hailed a game design group asking if any of them had a title available I could look at and talk about. He raised his hand. Ta-da. A title from the maverick and inventive Hollandspiele imprint no less, which I’ve been overdue to sample.

Except in my enthusiasm, I forgot that moving to this part of the world made me a solo player. My opponent crapped out after the second round. (See: Hazards of external dependencies.) A bit of intention, curiosity and focus across the table is so critical for a two-seater game.

Sometimes I feel like a goddamn child who can’t remember anything, thinking I’m going to buy some “magic game” that’s going to create interest where there isn’t any, like I don’t have the dusty carcasses of previous multiplayer titles stacking up in the spare room. You think I’d learn.

Anyway, what I’m talking about here are intriguing things where my limited experience seems to point.

For one, that dry-erase board was filling up fast. The cards used for tricks get removed from the game. It was easy to see how two people could grind their teeth quite a bit playing this as a straight-ahead competitive area control game as the board closes. The diplomat who can track and analyze the dwindling possibilities could make their opposite’s life pure hell.

Except: The rules also suggest more fluid spaces to feel out. There are rules for negotiation — a dimension my exhausted playtester and I never even tried as we were just learning the basics. OR: As the designer also reminds us, you can also choose to play cooperatively.

Would that include, for example, using the abstracted dry-erase board to see if you challenge each other to fill it in while leaving key cultural sites alone? There seems to be explicit permission for creative subversion, a chance to play in an imperial sandbox without being bound by imperial logic. Unfortunately, the intriguing nuance of Sykes-Picot will remain hidden from me as long as keener opponents do. It is my hope to explore this fascinating and tragic duel again.